Women have been at the forefront of AFSCME’s agenda, but increased organizing and the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s made their concerns an even higher priority. Through the work of its locals, various national committees and a Women’s Department, AFSCME has acted on issues important to women, not least of all sex discrimination in the form of pay inequity.

This played out most spectacularly in San Jose, California, in the late 1970s. Municipal workers in Local 101 were unhappy about the low pay offered for jobs primarily held by women. They saw an opportunity when the City of San Jose studied managerial wages and concluded that managers were underpaid. City leaders adjusted management salaries accordingly. Local 101 pushed for a similar study for non-management positions.

The local had support and guidance from AFSCME International and AFSCME Council 28, which had led efforts for a pioneering wage study of Washington State employees in 1973. The San Jose report was completed in 1980. That study, and others like it, looked beyond the notion of equal pay for equal work and instead focused on a job’s comparable worth. Each job received a score based on a number of factors to determine its “worth” to the city. This allowed the city to compare the jobs predominantly held by women to those held mostly by men that received the same score. The results were clear – women working for the City of San Jose were significantly underpaid.

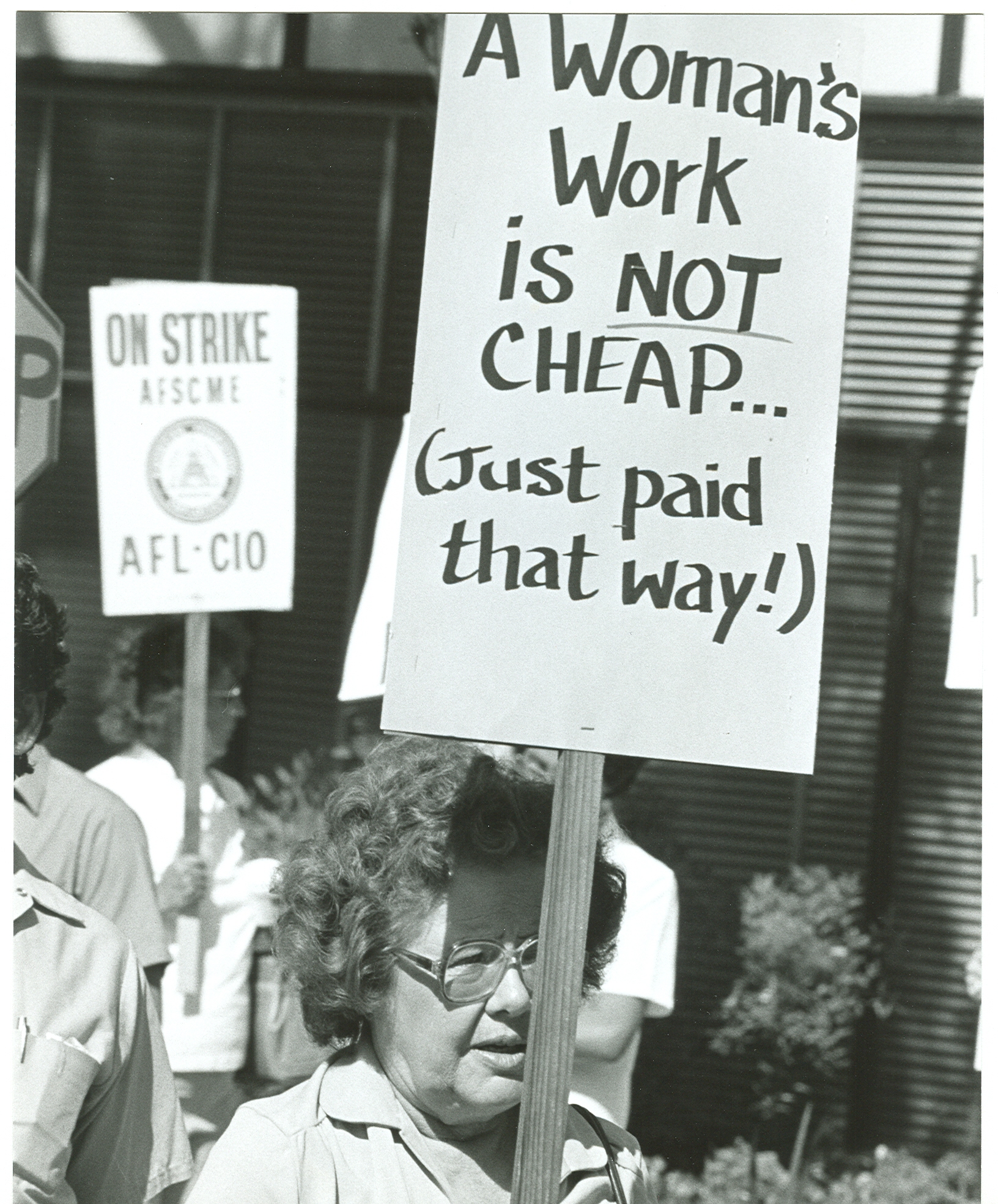

By then, Local 101 was preparing to negotiate a new contract. Even with the evidence staring them in the face, city leaders could not reach an agreement to correct the wage disparity. In July 1981, Local 101 went on the nation’s first strike over pay inequity. The city manager sent pink slips to the striking workers. Undeterred, they picketed outside his office and burned the pink slips on a grill. After they picketed for eight days and with the national spotlight on San Jose, the city and the union reached an agreement. The underpaid job classes received equity raises in addition to all employees receiving general raises.

Local 101’s success ignited the fight for pay equity across the United States. In Washington State, Council 28 continued to press for action on its 1973 study. Council 28 filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and then filed a lawsuit, which resulted in equity raises in 1985. Minnesota passed pay equity laws for state and municipal employees, thanks in part to the efforts of Council 6. Many AFSCME locals across the country won their own battles for pay equity. AFSCME President Jerry Wurf declared comparable worth “the economic issue of the 80s.” But gender-based pay inequity remains a problem to this day, as women still earn only about 83 cents for every dollar a man earns.