Front-line workers across the U.S. are heading into hospitals and other high-risk zones knowing that the likelihood of being infected with COVID-19 is incredibly high. For hospital workers in New Jersey, these risks have been all too real – and made worse by what they say are the slow an inadequate responses from hospital administrators and the New Jersey Department of Health.

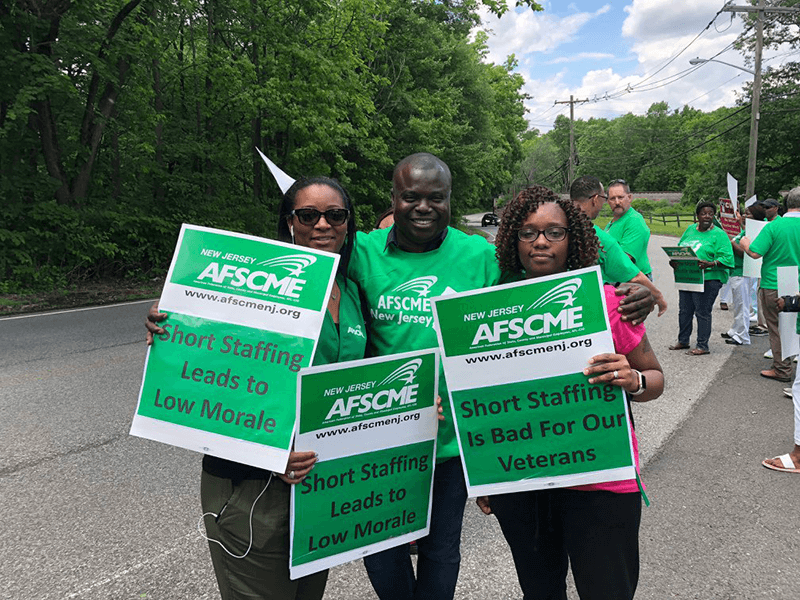

Awol Alhassan, a human services technician at Ancora Psychiatric Hospital and president of Local 2218 (AFSCME New Jersey), is among those who has COVID-19.

As of today, New Jersey had nearly 132,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases and more than 8,500 deaths, with many of the outbreaks occurring in facilities like the one where Alhassan and the members of Local 2218 work.

Alhassan says he was forced to work with little to no personal protective equipment (PPE) and in close proximity to infected patients.

“I was working on a unit that had two prospective COVID patients, but there was no real isolation,” Alhassan said, noting that one of the patients later tested positive.

Isolation policies were nonexistent in the hospital, he says. For instance, the prospective COVID patients could use the general bathroom rather than being separated into areas with isolated bathrooms, he says.

Alhassan worked with AFSCME New Jersey Executive Director Steve Tully and other allies to press the state Department of Health for more action – all while at home, recovering from COVID-19.

“I outlined a plan for them, and I told them I know we can do this, it’s not too late,” Alhassan said.

His plan calls for using on-hand materials and adjusting current practices to ensure better safety with relatively little disruption and cost.

“We have been constantly pressuring the state to prioritize the health and safety of our members and the patients,” Tully said. “We have been demanding that they implement appropriate screening procedures and supply the PPE that our members need. The truth is some facilities and departments have been better than others.”

For Alhassan, the safety of the patients as well as fellow workers is his highest priority. Under his leadership, Local 2218 organized the purchase of $8,000 worth of N95 masks for workers at the hospital after the Department of Health and hospital officials failed to provide masks.

It was only in mid-April that health screenings of staff began – after over 40 staff members and nearly 40 patients had been infected by the virus, Alhassan says. Further, without proper isolation procedures, the number of those likely infected but not confirmed to have COVID-19 is a huge unknown, he says.

Stories like Alhassan’s are not isolated within New Jersey – COVID-19 deaths at nursing homes and a veterans home have made headlines – as health care facilities adopt varying responses to the crisis. Throughout the country, wealth disparities have shortchanged institutions where people need more care and services.

Much of the burden of containing the virus in New Jersey – which has the second-highest number of COVID-19 cases after New York state – is on workers like Alhassan.

“Our members are on the front lines at all of our state facilities, making sure their patients and clients are protected,” Tully emphasized. “This situation is taking a tremendous toll on them both physically and psychologically. The state and every single employer in New Jersey needs to reward front-line workers with hazardous duty pay.”

For states like New Jersey, whose needs are dire and whose death tolls continue to climb, getting state and local relief through Congress is vital to providing the support that front-line workers like Alhassan and his team desperately need. Support AFSCME’s Fund the Front Lines effort.