What would you think of a financial adviser who suggested that the life savings of an 80-year-old Alzheimer’s patient be invested in such a way as to lock it up for at least 10 years – with no guarantee of advertised profits at the end of that period – and to receive a severe financial penalty for selling before the investment’s maturity date?

You’d think – find me another adviser!

Given the age and disability of the (actual) person whose investment money was at stake, such advice was not in that person’s best interest. She or he might need that money soon to pay for assisted living or nursing care, for instance. But under current law, it is not illegal for the adviser to suggest such an investment.

Unfortunately, financial advisers are not required to consider the “best interests” of their clients. That’s called “fiduciary duty,” which is legalese for putting the other person’s best interests first. In the case of the Alzheimer’s patient, it means doing the right thing, given the patient’s disability and age, among other factors. Instead, the financial adviser put his own interests first, as the investment he suggested would have garnered the adviser a hefty fee.

How do you protect yourself? Well, you could read all about the particular investment proposed, and if it’s not right, reject it and find another adviser. But that means you’re responsible, not the adviser.

President Obama had a better idea. In February 2015, he called for new rules to prevent retirement brokers (“investment advisers”) from putting their own financial interests ahead of their clients. As he explained at the time, “It's a very simple principle: You want to give financial advice, you’ve got to put your client’s interests first. You can't have a conflict of interest.”

This is a real problem, a conflict of interest that costs American families an estimated $17 billion in retirement savings losses every year, according to the White House Council of Economic Advisers.

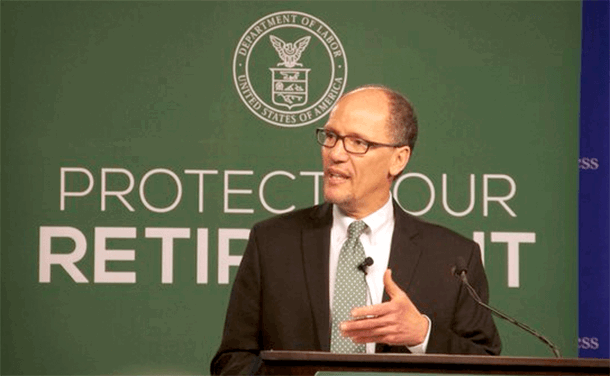

To protect investors, the Department of Labor recently issued a new regulation that requires investment advisers to provide advice in the best interest of retirement savers.

Great, right? Unfortunately, acting at the behest of Wall Street, Congress voted to block the regulation before it could begin to help retirees and those saving for retirement. To protect their legislation from a veto by the President, Republican leaders are trying to use a legislative tactic – inserting language opposing the rule into another, unrelated bill – so it would make it all the way to the President’s desk. They are betting that the President would not want to veto the entire bill to protect his regulation.

AFSCME, the AFL-CIO and allies such as the AARP are working to make sure the new regulation will go into effect. Every investor – whether saving for retirement or not – expects their best interest to be the guiding principle when investment advisers provide advice.