After selling off its dairy herd of more than 1,000 cows from state-run prison farms that supplied 1.3 million gallons of milk each year, Ohio taxpayers must now shell out $2.6 million a year to supply milk to 50,000 inmates.

“It's the biggest waste of taxpayer dollars I've seen in my 25 years as a state employee,” said Chris Mabe, president of Ohio Civil Service Employees Association (OCSEA)/AFSCME Local 11 and also an AFSCME International vice president. “It's an absolute giveaway at this point.”

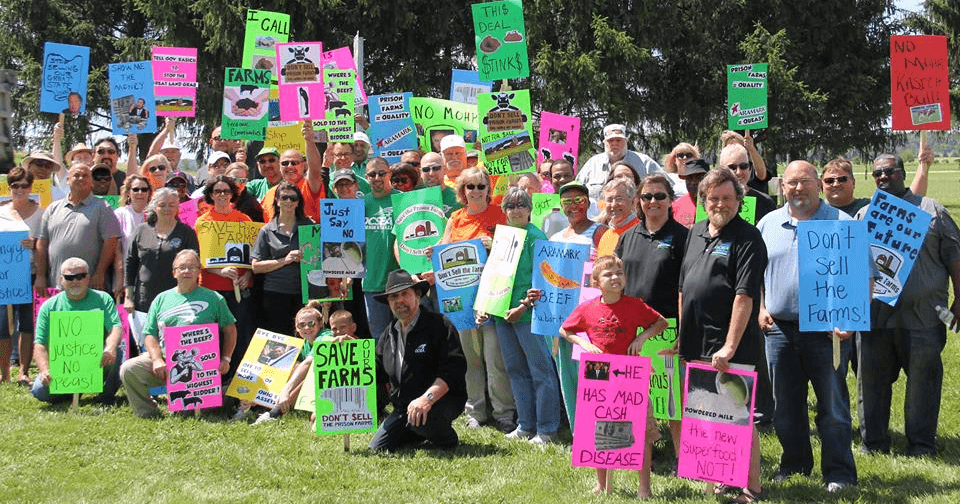

Since the Kasich administration’s corrections agency announced in April that it was getting out of the prison farm business, hundreds of OCSEA members have protested at each of the state’s 10 farms slated for closure and sale. The decision surprised employees, legislators and the public because the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (DRC) had already spent nearly $9 million to upgrade the farms.

OCSEA, which represents 72 state employees who supervise the inmates at those correctional facilities, filed a lawsuit challenging the sales, alleging a contract violation. The state responded by filing motions seeking to block the union from gaining information about the farm sale. A hearing was just held in a county court on a Preliminary Injunction to stop the sale. A decision on the injunction is pending.

Prisons Director Gary Mohr cited security concerns as reasoning for closing the farms, but some have suggested ulterior motives: that corporations cozy with the Kasich administration are eager to snap up 7,000 or more acres of farmland at the 10 sites.

Under the guise of “improvements,” the Kasich administration outsourced prison food services at a cost to taxpayers of $110 million. Now run by Aramark, Ohio prisons have been the subject of confirmed reports of maggot-infested food.

The prison farms, in existence for more than 100 years, have been, for the most part, self-sustaining. The already completed upgrades were projected to increase both meat and dairy production to three times the current amount as well.

Crops are also grown to help supply food to local food banks. Inmates learn how to operate heavy machinery, weld and repair equipment, and use a variety of tools as well – skills they can use once they’ve served their sentence.

While prisons may not be turning inmates into farmers, some state employees argue it's all about teaching the inmates work ethic. “It's the act of teaching people responsibility, the value of working an eight-hour day and being able to be outside a fence,” Mabe said. “Even Director Mohr praised the farm operations a year ago. Something is not adding up here.”