Public service isn’t just a job — it’s a calling. And public service workers aren’t in it to get rich or famous but for the satisfaction of making a community better.

And yet when we go to work every day — whether we’re serving as nurses or corrections officers, teachers or sanitation workers, or in many other ways — we expect to be treated fairly and with respect. Most of all, we shouldn’t have to sacrifice our lives to serve our communities.

Yet far too often, that is what happens when worker protections fail.

Take, for example, the tragic death of Ronald Silver II, a 36-year-old sanitation worker for the city of Baltimore who died of overheating last summer while on the job. He died after warnings that he and his co-workers were not getting enough relief from high temperatures and lacked access to cold water, ice and air conditioning.

Three months later, Timothy Cartwell, also a sanitation worker for Baltimore, died tragically after he was trapped between a garbage truck and a wooden light pole.

The preventable deaths of these two AFSCME members are a reminder that we must do more to protect public service workers on the job. They are a reminder of the lessons of Memphis, Tennessee, 57 years ago.

The lessons of Memphis

On Feb. 1, 1968, two sanitation workers for the city of Memphis, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning city truck.

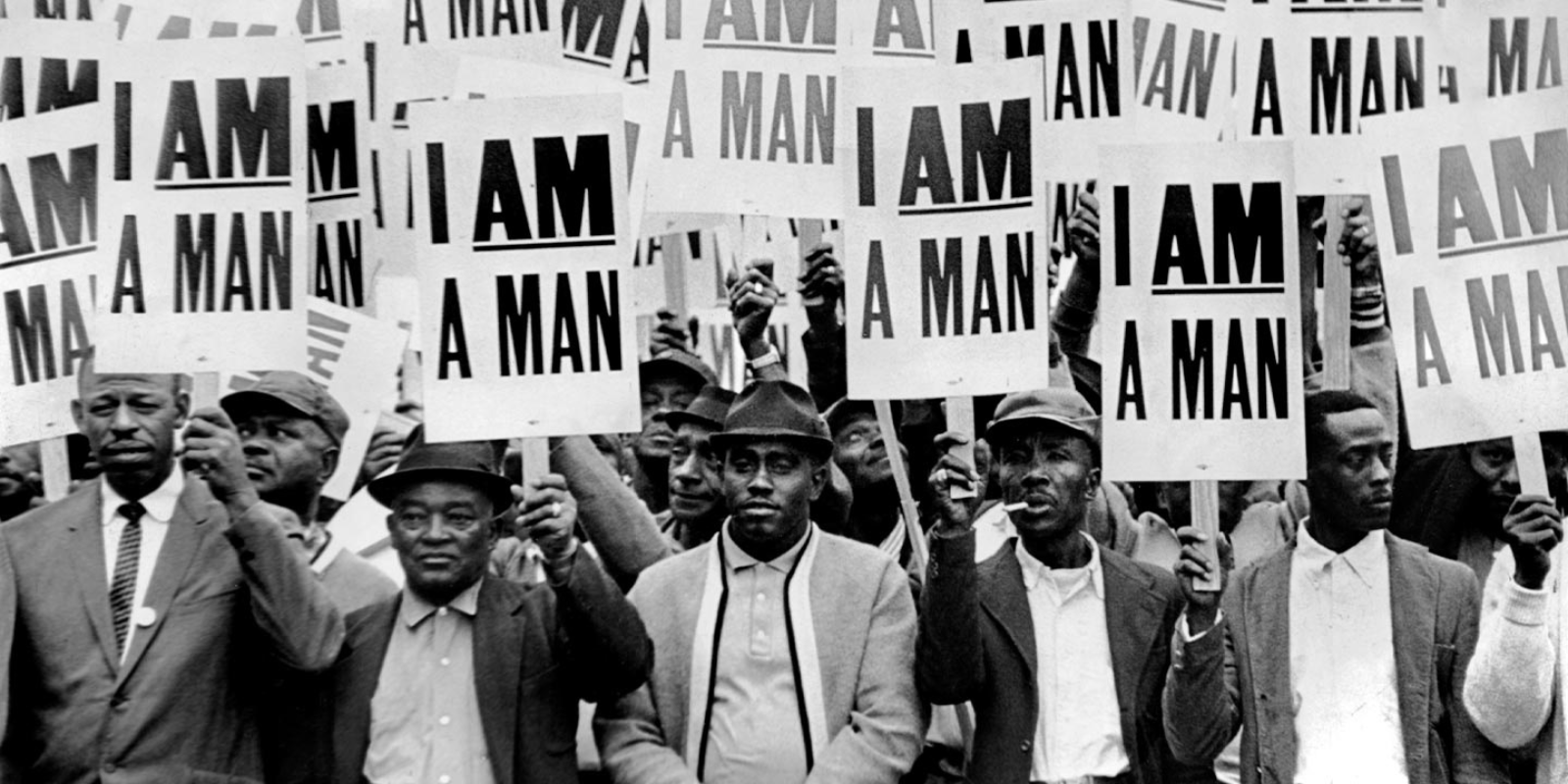

Angry and saddened, sanitation workers in the city went on strike, protesting dangerous working conditions and also demanding higher wages and dignity on the job. The workers were members of AFSCME Local 1733, though their union had yet to be recognized by the city.

The city’s mayor, Henry Loeb, declared the strike illegal and refused to negotiate with the workers. The city council sided with the mayor. Although the sanitation workers provided an essential public service, the message from their elected leaders was clear: you don’t matter to us.

But the workers did matter to their community. They mattered to their national union, AFSCME, whose president, Jerry Wurf, showed up to support them. They mattered to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), whose Memphis chapter endorsed the strike. They mattered to Black leaders and ministers who formed a citywide organization to support the workers.

And they mattered to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who joined the strike and addressed the workers on April 3, the day before he was shot and killed outside his Memphis hotel room.

On April 16, the strike ended when AFSCME leaders announced that they reached an agreement with the city. The workers voted to accept it.

The AFSCME sanitation workers succeeded in their struggle because they never quit, because they confronted the leaders of their city with the truth: that without the services they provided, the city could not function.

It’s time to Get Organized

This past fall, Maryland enacted a heat standard, but we need one nationally, too. AFSCME has been working toward a federal heat standard to protect public service workers on the job. It was about to go into effect, but then the Trump administration stopped it.

As the global climate rapidly gets warmer, the new protections would help address the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States. Between 2011 and 2022, there were at least 33,890 estimated work-related heat injuries and illnesses that resulted in days away from work, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

But we shouldn’t wait with arms crossed for the federal government to act. Public services matter and the workers who provide them deserve safe workplaces. AFSCME will continue our fight for a federal heat standard and safe working conditions — heeding the lessons of the past and the call of the Memphis Sanitation Workers strike to Get Organized.