HONOLULU – “Two months ago, placing a child in a foster home wasn’t a problem. Now it’s nearly impossible,” says Hawaii Child/Adult Protective Services Specialist Kalani Motta, a member of HGEA/AFSCME Local 152.

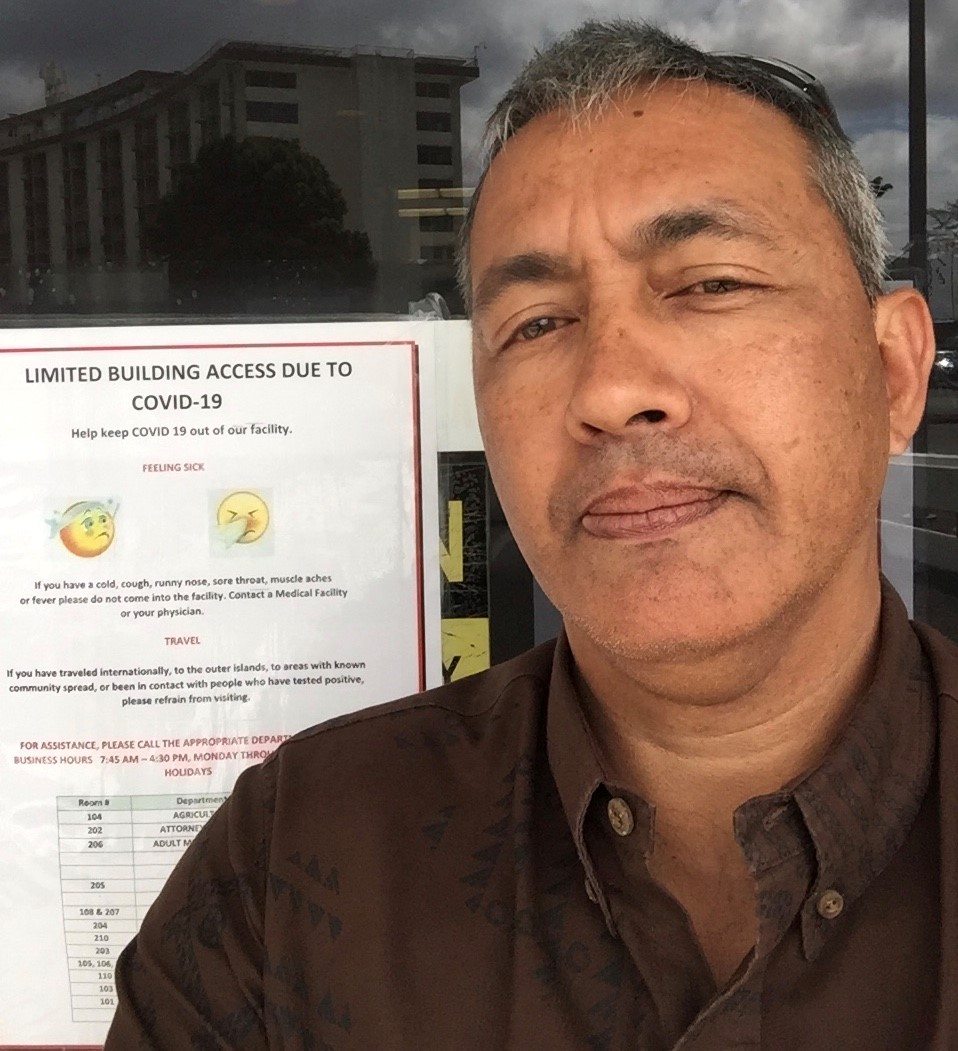

One of Motta’s primary duties as a case manager with the state Department of Human Services in Hilo is to find foster homes for children in East Hawaii. In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, he’s been classified as an essential employee, and although he was given the option to work from home during the crisis, the nature of his job doesn’t allow for it.

“Certain parts of this job, there’s no way you can work from home,” Motta says. “When we respond to calls of concern, we have to go out and physically locate the family. The only way we can help these children is if we get out there and do it in person.”

Before the pandemic, most of the calls Motta responded to typically came from schools. Now that students are not in the schools, the calls are coming in from the public.

“We still go out, we still investigate and try to place the kids in our care. Our responsibilities haven’t stopped because of the health crisis, but it’s much more stressful to maintain a high level of service,” he says.

Even more frustrating than the coronavirus itself is the lack of clear, consistent communication and the chaos it creates.

For instance, after employers were made aware of an incident where a courier allegedly tested positive for COVID-19, workers were told the building would be cleaned just one time.

“They told us the building would be cleaned for a few hours one day, but that’s not enough. And what does that even mean? How well was the building cleaned?” Motta wonders. “We’re considered essential but we’re not being provided with PPE [personal protective equipment], cleaning supplies or even clear information about what’s going on. The misinformation or lack of communication creates anxiety in an already stressful situation.”

Shared office spaces don’t always allow for adequate social distancing and employees often risk their personal health for the welfare of their clients, many of whom are minors in need of a place to live.

“We try to do social distancing in the office … but our whole department is essential. Some workers are given the option to work remotely, although most are coming in,” he says. “I think for all of us, our main priority is to protect our families – those we serve and those we go home to, but it’s hard. And I think everyone is feeling the same burden of wanting to do good work but also wanting to stay safe.”

Motta’s had to accept that “business as usual” just isn’t the norm anymore. He still attends hearings for his cases, but they’re no longer scheduled regularly. Review hearings typically scheduled every five or six months are being pushed back indefinitely, and only protective custody hearings or cases involving extreme circumstances are being scheduled.

Legal proceedings meant to help families aren’t the only resource Motta sees decreasing. He has a difficult time just getting basic health care services for his clients.

Some of the most wrenching changes he’s seen are with court-ordered visitations and the declining willingness of foster homes to take in new children.

“There’s no in-person visitation anymore. They’re all being done by phone or on FaceTime now,” he says. “It’s heartbreaking. Especially now when you’re trying to maintain the family time and relationships.”

Ironically, the social distancing measures meant to keep us away from one another are working too well.

“Foster parents are stressing out, and reluctant to take new kids into their home, so we’re doing our best, but it feels like we’re using chicken wire and zip ties,” Motta says about the temporary solutions being used until he can find a safe, permanent home for foster children.