When I came across this letter, dated Sept. 8, 1967, in the AFSCME Local 1: Washington, D.C. records, I immediately wanted to know more. Who was Marvin Fleming? What did he go through? Where is he now? How many other stories are out there of people smashing pernicious forms of discrimination that we don’t know about?

The letter continues with some clues: “Over the determined resistance of Mr. Roeder, Division Chief, and Mr. Redd, Chief of the Incineration and Trash Collection Branch, Mr. Fleming was able to receive on-the-job training as a Crane Operator without first serving an apprenticeship as a Weighmaster. He has since been the subject of repeated harassment.”

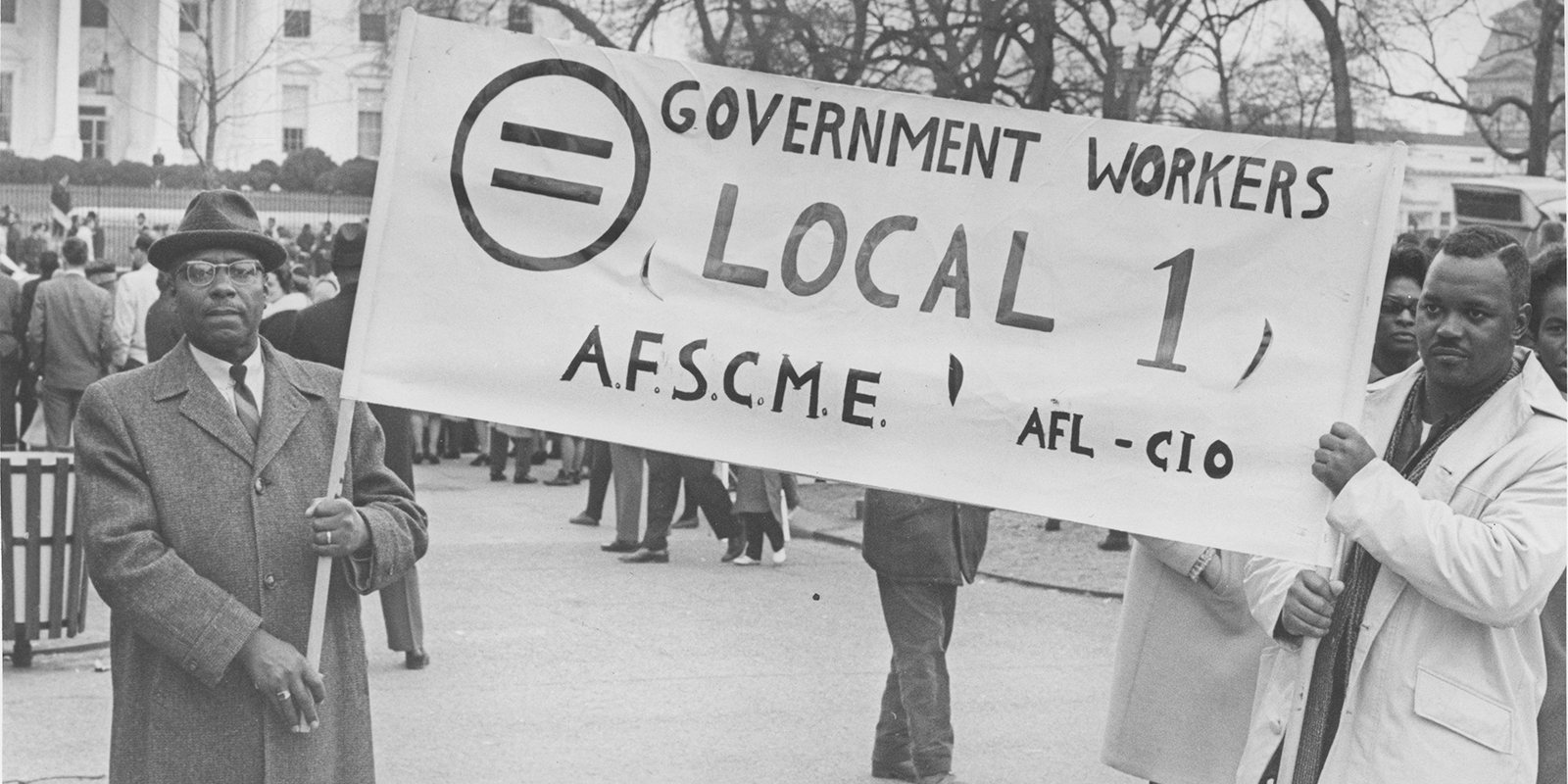

Marvin Fleming was a member AFSCME Government Workers Union Local 1, Washington, D.C. The local consisted of employees in the departments of Public Health, Public Welfare, Buildings and Grounds, and Sanitary Engineering.

Since at least 1960, the local began to push hard against racist practices within the D.C. government. The April 1966 issue of AFSCME’s Public Employee magazine said, “… job discrimination was a basic fact of life. …The Division of Sanitation was worst of all. Not even token steps had been made toward opening the higher grade, skilled jobs” [to Black men].

Warren Morse, business agent for the union who handled member grievances, noted in 1964 that most of the 1,600 sanitation workers in the District were Black, and yet the higher grade positions were primarily occupied by white men. For a long time, until the union got involved, there was no formal promotion policy at all, resulting in nepotism and the promotion of white workers far more often than Black workers.

Morse charged that when white men were hired for entry-level jobs, they were assigned tasks like fetching coffee. They had extra time for on-the-job training to learn higher-skilled tasks, enabling them to be promoted. Meanwhile, Black workers completed the “dirty and arduous tasks” such as trash collection, sweeping floors and cleaning trucks.

One of the higher skilled jobs was that of crane operator. To be a crane operator, you first needed a promotion to weighmaster. To be weighmaster, you had to know how to operate a crane. Since Black workers were not able to get that on-the-job training, they were effectively shut out of the promotion process, according to a Nov. 18, 1964, letter. The union recommended a formal training program to make the higher grades accessible to all. Though the Sanitation Division initially agreed, they did not follow through until the Local 1 pressed for it.