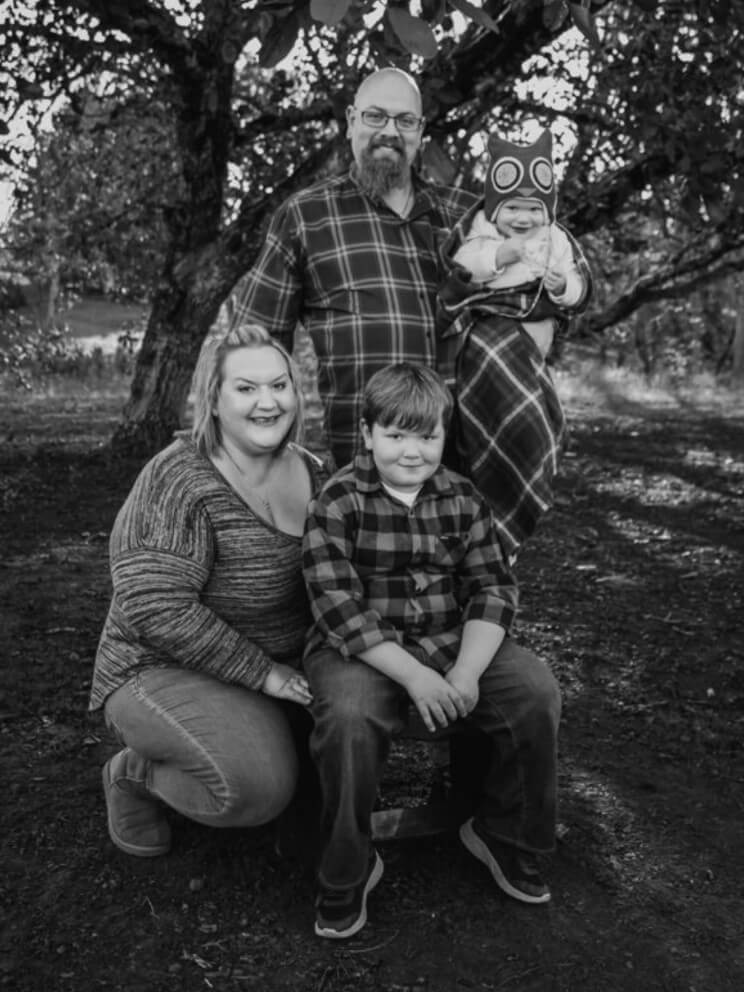

Liz Sabin never thought she’d have to rely on her sister to take a sick day from work to care for Sabin’s children, who are 2 and 7 years old. But that’s where she’s at.

Nine months into the coronavirus pandemic, Sabin, a nurse at Coffee Creek Correctional Facility in Wilsonville, Oregon, and a member of Oregon AFSCME (Council 75), is still scrambling to find adequate child care. When schools first shut down in the spring, her husband took four months of unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act.

Later, Sabin herself was able to take paid leave through the CARES Act, passed in March in response to the economic fallout of the pandemic. Things might get better in January when her husband begins a new work shift but, having burned through a lot of paid vacation leave and with the prospect of a long, dark winter ahead, it’s unclear just how much longer they can sustain this.

“I don’t want to be part of the problem, I want to be part of the solution,” Sabin says. “But employers could do a little bit better job of working with employees to help them cover child care. You can’t leave small children alone. That’s just not an option.”

Sabin is hardly alone among public service workers on the front lines of fighting the pandemic. Nurses, first responders and other health care workers, as well as essential workers from behavioral health to sanitation workers, do not have the option of working from home. Parents need child care more than ever, even as many of them have lost wages and face limited child care options.

Child care workers themselves are in no better position. Many of them have lost their jobs since the pandemic began, and the child care programs they run are struggling to stay afloat.

Rachel Lamet, who runs a child care business out of her home in Salem, Oregon, and is also a member of Council 75, says her small business isn’t sustainable anymore.

“I’m not making any money at all, I’m probably losing money,” she says. “I’m in my home and my husband pays the bills, that’s the only reason I’m still up and running.”

Her registered family child care is licensed for a maximum of 10 children. When the pandemic first started, she lost all of the families she was serving. Now, most of them have come back, but the money she has spent all these months on cleaning supplies and additional expenses to meet the new emergency regulations have put her in the red.